Friday, September 15, 2006

Agatha Christie is born in 1890

In 1873, the last German troops leave France upon completion of payment of indemnity.

Born Mary Clarissa Agatha Miller in Torquay, Devon, England, Agatha Christie wrote 80 novels, 30 short story collections, 15 plays, and 6 romances under the pen name Mary Westmacott. Knighted in 1971, she died in 1976 with more than 400 million copies of her books sold in more than 100 languages.

It was during WWI, when her husband, Colonel Archibald Christie was fighting, that she learned about poisons while working in a pharmacy. Her first novel, featuring Hercule Poirot, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), did OK, but it was her 2nd one, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) that was a bestseller and where she began her lifelong success.

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=4092

http://uk.agathachristie.com/site/home/

http://christie.mysterynet.com/

http://www.online-literature.com/agatha_christie/

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Civil War Ladies' Hairstyles and Hair Accessories

Oh, say can you see?

http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0194015.html

http://americanhistory.si.edu/ssb/

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

A Few Ladylike Activities

* charity work any or every day of the week with her church or favorite charitable society

* spending mealtime or teatime with other ladies of leisure and literary writers

* reading aloud in her chambers with other ladies, especially during the time for after dinner drinks and smokes

* feeding the birds at parks and common areas, especially during the Wintertime.

Kristin-Marie

The Union Discovers "Lost Order"

9/13

In 1862, “Union soldiers [found] a copy of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's orders detailing the Confederates' plan for the Antietam campaign near Frederick, Maryland. But Union General George B. McClellan was slow to act, and the advantage the intelligence provided was lost.”

Sergeant John Bloss and Corporal Barton W. Mitchell found a piece of paper wrapped around three cigars, realized what it was, and passed it up the chain of command. Purely by accident, the division adjutant general, Samuel Pittman, recognized the handwriting (it was from a colleague from the prewar army, Robert Chilton) who happened to be the adjutant general to Robert E. Lee. Pittman took the paper to McClellan. McClellan crowed at his potential victory.

And then he did nothing.

He thought Lee had greater numbers than the Confederates actually did, took 18 hours to get his army in motion, and to top it all off, Lee was alerted to the approaching Federals, and sent troops to plug the gaps in his own army.

The press dubbed McClellan "Mac the Unready" and "The Little Corporal of Unsought Fields".

Ordered to relinquish command from the War Department, McClellan did so on Nov. 9, 1862. In true New Jersey fashion, he then went on to play an active roll in state politics. Yeah, we haven’t had a good governor in centuries…

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=2317

http://www.civilwarhome.com/macbio.htm

http://www.nps.gov/archive/anti/mccl-bio.htm

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Don’t take candy from a stranger.

In 1898, Elizabeth Dunning (daughter of a US Congressman and wife of John Dunning, bureau chief for the Associated Press) and her sister, Mrs. Joshua Deane, died after 3 days of terrible stomach pains from consuming a box of chocolates from a Mrs. C, whom she did not know. (I won’t even ask why she’d do such a stupid thing as eat something from someone she didn’t know, but apparently signing the letter Mrs. C convinced Elizabeth it was from a friend.)

Dear John was having an affair with Cordelia Botkin while he and Elizabeth were living in San Francisco. Elizabeth found out, left John who left Cordelia. None too happy with the end of the affair, Cordelia sent letters to Elizabeth claiming the affair continued (long distance, apparently).

Convicted in 1899 of intentional poisoning by Arsenic, Cordelia received special treatment – overnight male visitors, a lushly decorated cell, and 2 days a week into San Francisco. Eventually these privileges were revoked, and Cordelia died in San Quentin in 1910.

http://www.well.com/~sfflier/Botkin.html

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=1124

http://www.russpickett.com/history/botkin.htm

Monday, September 11, 2006

Oh! Susanna

Most of us know what happened today in 2001. (http://www.theseptemberproject.org/ and http://www.september11news.com/) I’m lucky to be able to remember this day with a happier spin because my niece was born in 2003, so we celebrate life on such a tragic day.

Steven Foster’s 1847 hit song was first played at a Pittsburgh saloon. It was a national hit and became the unofficial anthem of the 49ers - the miners during the California Gold Rush, not today's football team *G*.

Foster wrote several other classic popular songs, including De Campton Races (1850), Old Folks at Home [Swanee River] (1851), My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night! (1853), Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair (1854), Gentle Annie (1856), Beautiful Dreamer (1862), and The Voices That Are Gone (1865).

Something I had no idea about until researching Foster for this blog. According Ken Emerson, Foster’s biographer and the All Music Guide:

“It became associated with the California Gold Rush. Yet most people don't know

many of the words--fortunately, for the song was actually a blackface dialect

number whose words contain some appallingly racist lines. However, a little

thought also makes the song's subtext clear: the singer clearly identifies

himself as an African American, yet he blithely sings of coming from Alabama,

travelling freely by riverboat to New Orleans. For all its lightheartedness,

"Oh! Susanna" depicts a slave's escape attempt.”

http://www.answers.com/topic/oh-susanna-vocal-classical-work http://www.pdmusic.org/foster.html

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=3606

Sunday, September 10, 2006

British police make first DWI arrest 1893.

September 10.

Apparently, it wasn’t difficult to tell that George Smith was drunk while driving. The swerving gave him away.

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=7655 http://qualityweenie.mu.nu/archives/090321.php

Friday, September 08, 2006

First Lady gives birth to daughter!

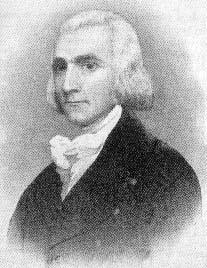

It was a tough choice today – President Grover Cleveland’s baby’s birth, or California becoming the 31st state.

I chose the baby only because it was a first. Frances Cleveland (27 years younger than her husband and the youngest First Lady in history) was the first First Lady to give birth in the White House. Daughter Esther is the first – and only – child born to a president in the White House, on September 9, 1893. Of course Grover Cleveland was also the first president to be married in the White House (though not married while in office) and the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms.

[picture: http://encyclopedia.quickseek.com/images/President_cleveland_wedding.png]

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=50965

http://www.americanpresident.org/history/grovercleveland/

http://www.worldbook.com/features/presidents/html/cleveland_frances.htm

http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/gc2224.html

Hurricane Hits Texan Coast (aka Isaac’s Storm)

Since wind gauge blew away, wind speed might have been higher.

Isaac Cline was the chief weatherman for Texas, at a time when it the U.S. Weather Bureau was inundated with scandal. (Embezzlement and escape from prison, unable to accurately predict the weather to the point where astrologers were listened to more than weathermen…you get the picture.)

In an article written a few years before, 'Cline boldly declared a cyclone could never seriously' damage Galveston; anyone who thought otherwise was delusional. What he didn’t realize was that when cables arrived at the Washington Bureau headquarters about the storm off the Cuban coast was that this storm wasn’t like others that hit the Gulf.

It was a mistake that cost Isaac his wife.

Of course, hurricane forecasting technology of 1900 mainly consisted of ships at sea telegraphing into the mainland their approximate location (if they hadn’t been tossed about too much) and that they’d encountered a hurricane. To read more about this national disaster that was worse than the1906 San Francisco earthquake or the 1889 Johnstown Flood in Pennsylvania, try Isaac's Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History by Erik Larson (Paperback: 0-375-70827-8).

http://www.history.com/tdih.do?action=tdihArticleCategory&id=50831

http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutsshs.shtml

http://www.1900storm.com/isaaccline/isaacsstorm.lasso

Thursday, September 07, 2006

“A Victorian Reborn”

http://www.history.com/classroom/victorianreborn/

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Victorian Gardens

In Regency times, Humphry Repton had established the flower garden around the house. His style of gardens often contained rustic elements of grottos and ruins for pictorial effect, called the Picturesque style landscape. John C. Loudon developed the Gardenesque style and advocated the use of ornamental shrubberies, bedding plants, exotics, and a formal design that made each garden a work of art. But these gardens were limited to the wealthy.

By the Victorian period, the industrial revolution was at its height. The middle classes had more leisure time. Improved roads and transportation made it possible for wealthy middle classes to build villas on the outskirts of town where the air was cleaner. Seeking to display their wealth, they created showy gardens rather than landscapes that would harmonize with their location. Better printing systems allowed the spread of horticultural knowledge and inspiration. Edwin Budding’s lawnmower meant people were able to manage manicured lawns. The Allotment Act in 1887 made space for growing plants available to city dwellers at a reasonable rent.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 demonstrated the continued enthusiasm for new technologies and designs. Joseph Paxton created the Crystal Palace, for which he was knighted by Queen Victoria. Paxton also designed the new conservatory at Chatsworth and later sold small greenhouses to amateur gardeners, which, among his other business interests, made him a millionaire. By the late Victorian era, heated conservatories displayed rare exotic plants. The middle Victorian garden style was eclectic, varying from Chinese to Italianate. By the late period, fantasy-themed gardens were popular, as were those celebrating the British empire. The garden gnome made its debut along with other garden ornaments. Japanese influence increased the demand for acers, flowering cherries, peonies and chrysanthemums. The garden became a place for family pursuits, such as tennis and croquet.

The Victorian period was the golden era of plant collection. British archeologists were risking their lives to bring back artifacts from all over the globe, and botanical adventurers were returning with plants from around the world. Brothers William and Thomas Lobb were among the Victorian plant hunters. William recovered plants form North and South America while Thomas traveled to Indonesia, India, and the Philippines. George Forrest traveled to China, Tibet, and Burma and was responsible for introducing about 600 species of plants including rhododendrons, camellias, magnolias, Himalayan poppies, and primulas. Joseph Hooker brought more species of rhododendrons from Himalaya. Robert Fortune disguised himself as a Chinese peasant and smuggled out cuttings of the tea plant from China into India, which enabled India and Ceylon to become established as major growers and exporters of tea. He also introduced 120 species of plants from China and Japan.

According to the Royal Horticultural Society, ornamental plants popular during Victorian times included: Monkey puzzle, many species of fern, Mexican orange, Rose box, helix ivy, bamboo, slender vervain, silver ragwort, blue marguerite, fuchsia, heliotrope, trailing lobelia, pelargoniums, gentian sage, hornbeam hedge, katsura tree, edelweiss, Scots pine, Japanese snowball, araranthus, calendula, cornflower, satin flower, cosmos, California poppy, Gilia, sunflower, Virginia stock, baby blue eyes, Californian bluebell, phlox, and nasturtium. Vegetables included: broad bean, cabbage, cardoon, carrot, French bean, leeks, lettuce, onion, parsley, peas, radish, salsify, sea kale, and turnips. I was amazed to see North American plants like California poppies and bluebells, yucca, and others I think of as only grown in the Southwestern United States , Central and South America.

According to Cheryl Hurd, Victorian gardening was comprised of eight elements. 1. A front and rear lawn were imperative for a formal garden. Cottage gardens were more informal and smaller. 2. Trees were used to shade important parts of the house and to line the drive or approach to the house. Ornamental trees were popular. 3. Shrubs were used mainly for delineating property lines or marking paths. They might also hide unsightly areas or frame doorways. It was popular to mix shrubs. 4. Most properties were fenced. The more elaborate the home, the more elaborate the fence and gate. 5. Ornaments such as urns, sculpture, fountains, sundials, gazing balls, birdbaths and man-made fish ponds were all used. 6. Seating benches, seats, pavillions and gazebos were as decorative as possible. Rattan and wicker furniture was used on porches and in sun rooms. 7. Carpet bedding, the use of same height flora, was popular until Gertude Jekyll became popular. She believed each flower and plant should be grown for its intrinsic beauty and a border called for plants of varying height—lowest at front. Roses were extremely popular. 8. Vines of all types were used.

Those interested in specific gardens and influential designers of the era should read about Gertrude Jekyll, William Robinson [author of The English Flower Garden], Sir Joseph Paxton, William Andrew Nesfield, and John Claudius Loudon.

References:

"Victorian Gardening," by Cheryl Hurd, The Victorian Era Online, http://www.victoriana.com/

"Garden Highlights," The Royal Horticultural Society, 2006, www.rhs.org.uk/gardens

"A History of British Gardening," BBC Gardening, www.bbc.co.uk

Gertrude Jekyll's Lost Garden, Rosamund Wallinger, printed in England by the Antique Collectors' Club Ltd. Woodbridge, Suffolk, Garden Art Press, 2000.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

Faithless Mistress: Victorian Human Rights Symbol

Times were changing during the Victorian era for nearly every echelon of Society. Although formal mistresses were historically prominent in their roles, due in large part to the experiences of Ludwig I of Bavaria and Lola Montez, Victorian mistresses began to be tucked away, discreetly. In previous centuries they had ruled the proverbial roost, if only temporarily, but jittery Aristocracy decided to care for public opinions.

In 1847, in exchange for her role as royal mistress, Lola Montez was created the Countess of Landsfeld and awarded trappings provided by the State, which unsettled the highly religious and penny-conscious German citizenry. But King Ludgwig was in love, and had been duped into believing his mistress was true to him and somehow deserving of a gift of rank.

The German people cried out against Lola, not because of her low background as a dancer from Ireland - the fact of which had gathered a fan club from a University about her that chose to view her as a symbol of human rights worth rioting over – but rather, the people railed against paying for yet one more monarchical affaire. Unlike the King, the populace knew Lola for a selfish and manipulative woman. Ludwig abdicated for her, but discovered during the process that she was unfaithful on many accounts. As a result, she was exiled and left for America.

Lola made an historic splash as a notorious celebrity. Despite the ill omen of breaking a monarch’s heart and of being exiled after only sixteen months as mistress, Lola arrived in America heralded by newspapers and awaited by throngs. She had reached celebrity status across an ocean for her reputation as an adventuress. Living eventually in the Gold Country and dancing for a living for miners and investors, alike, she was retired to a quaint cottage in Grass Valley, California. Lola was known for her famous and sensual Spider Dance that wooed many a fresh admirer. A nicely pictorial sight about Lola is http://www.zpub.com/sf/history/lola.html.

Since Society was still holding its cumulative breath as the final results of the French Revolution were decided, despite a number of belatedly exonerated members of Aristocracy returning to the top, when the People decidedly objected to supporting mistresses through the State coffers, members of Society began to bow out. Notably, Queen Victoria’s son kept his mistresses more circumspect, as a result. Society’s gentlemen followed suit. Gone, it seemed, were the days when the most prestigious and prominent parties were hosted by a blueblood’s latest mistress, dressed to the Nines and intentionally outshining all other women and wives in the room. A useful book for comparative anecdotal passages about royal mistresses is Sex with Kings, by Eleanor Herman, ISBN #0060585440.

Once considered an indispensable accessory for centuries, men who could afford the trappings of a mistress during Victoria’s reign were less inclined to flaunt them over their wives. The more clever of men unwilling to give up mistresses were engaging financial planners for them to develop income sources that weren’t out of sacrosanct coffers or traceable from their own ledgers.

By Kristin-Marie

Friday, September 01, 2006

Victorian Wallpaper and Arsenic

Anyway, particles would be brushed off of this wallpaper accidentally and end up being ingested. This brings up an interesting question for those of us who tend to murder people in their books (that would be me). Arsenic seemed to be the poison of choice in the Victorian period. Could you blame the arsenic poisoning on the wallpaper?

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Passionate About the Civil War

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Great Exhibit Appealed to Victorian Sentiments

Ambitious and regarded as suitable work for a monarch to expend great levels of energy developing, the World Fair showcased the famed Crystal Palace exhibition hall which was ostensibly inspired by a noble’s topiary garden. During January of 1851, cart-horses were utilized to raise trusses for the central aisle of the steel and glass “Crystal Hive.” The exhibit got underway.

A quick link for statistics on the Great Exhibit can be found at http://www.earthstation9.com/index.html?1851_lon.htm

Due to the fact that the Exhibit was closed on the Sabbath, Sunday, only the wealthy and privileged were able to attend. (Commoners who worked six days a week were seldom allowed days off, except for Sundays.) Millions of attendees traveled mostly by railway from theoretically every country, since every nation was allowed to showcase their arts and industry.

Many Victorian era journals recorded the thrilling moments of attending the Great Exhibit, experiencing the wonders of the future on display. Whether drawn by nouveaux artists’ sculptures, on the one hand as the nobiliary Rothschild’s recorded of their experiences, or by the new technology on display, attendees were not disappointed.

Kristin-Marie

Saturday, August 19, 2006

VICTORIAN FASTLANE: Part 2, Two Astor Women - "Lina" and Nancy

"Lina" and Nancy Astor were obviously different sorts of women - their personalities, appearances and lives were worlds apart. But, in three ways, they were alike - each was born in the Victorian era, each married an Astor, and each became more famous and influential than her husband.

"Lina" was the former Caroline Webster Schermerhorn (1830 - 1908). She was a member of New York's Dutch aristocracy, the descendants of the city's original settlers, and she married somewhat beneath herself when she became Mrs. William Backhouse Astor, Jr.

For the first few decades of her married life, Lina was typical of her class and time - she was preoccupied with raising her five children and running her household properly. In 1862, she and her husband built a fashionable brownstone mansion. It occupied the land where the Empire State building now stands, and was next door to her husband's older brother, John Jacob Astor III. The two families were next door neighbors for 28 years - but the brothers didn't get along.

After the Civil War, New York grew at an astronomical rate, and keeping the nouveau riche would-be socialites in their place became Lina's new cause. Her husband, a notorious womanizer, had little interest in Lina, their marriage, or the "social whirl," so Lina threw herself into her new mission. She took on the burden of being the unchallenged grande dame of New York's estalishment, and demanded that she be addressed as "The Mrs. Astor."

Working with her distant cousin, Ward McAllister, a so-called social arbiter, Lina came up with "The Four Hundred," the only people who counted, the only ones who belonged to New York's "Fashionable Society." Lina and Ward didn't arrive at the amount based on the size of Lina's rather small ballroom, but that's still accepted as the origin of the magical number.

In 1883, Lina's world began to crack around the edges. The barbarians (the Vanderbilts) were at the gates. For her housewarming party, Alva Vanderbilt planned a costume ball with "entertainments" given by young society figures. At the last minute she sent word that Lina's youngest daughter, Caroline, couldn't participate, because Mrs. Astor had never formally called on Mrs. Vanderbilt. Lina chose her daughter's feelings over her own social position and took her calling card to Alva Vanderbilt.

This was only the beginning of Lina's fall from power. In 1890, her brother-in-law, who had lived next door for so long, died. His son, William Waldorf Astor, inherited his father's holdings, and by all rights, should be considered the head of the Astor family. He wanted his aunt Lina to stop using the "title," The Mrs. Astor. Lina refused and the New York papers sensationalized the conflict.

After William Waldorf Astor was defeated in his bid for a seat in the United States Congress, he decided to leave New York and his disagreeable aunt behind and move to Great Britain. He later became a viscount, but he left a parting gift for Aunt Lina. He had his father's mansion torn down and replaced with the first Waldorf Hotel. Lina was devastated. She told people "There is a glorified tavern next door."

In retaliation, Lina and her son, John Jacob Astor IV, considered tearing down her mansion and replacing it with a livery stable. But the opulent new Waldorf Hotel revolutionized how New York socialized. Unwilling to live next door to New York's latest sensation, Lina and her son tore down her mansion and replaced it with another hotel, the Astor. The two hotels later merged and became the first Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

By the time she moved into her new house facing Central Park, at the corner of 65th Street, Lina's husband had died. She lived with her son and his family until her death at age 78.

Down in Danville, Virgina, far from New York City, Nancy Witcher Langhorne was born in 1878. She was one of the five clever, beautiful and vivacious Langhorne sisters, Southern belles who became famous beauties. Lizzie, Phyllis, Nora, Irene and Nancy were the daughters of Chiswell Langhorne and his witty wife. A planter who had lost everything in the Civil War, "Chissie," made an even bigger fortune in railroads before Nancy was five, so the girls grew up with every advantage.

A big influence in Nancy's early life was Archdeacon Frederick Neve. Educated at Oxford, he came to Virginia to help poor whites in the interior mountains. Nancy worked with him as much as her father would allow and gained her first taste of a more charitable life.

The family also produced three sons, but they were eclipsed by their well-known sisters and little is known of them today. Early on, the lovely Irene was the sister in the limelight. She was the Gibson Girl who married Charles Dana Gibson. He was the famous illustrator and New York's most eligible bachelor until he met Irene, who was dubbed a Virginia society belle by Northerners.

Outspoken Nancy went to New York to finishing school as well, but she was labeled a "rustic fool" by New Yorkers. Irene tried to alleviate this by taking Nancy everywhere she went. Unfortunately, this led to Nancy's meeting and marrying Bob Shaw. Their marriage was a disaster. It lasted four years and produced one son, Robert Gould Shaw, III. The marriage ended after he agreed to the condition that his adultery would be stated as the cause of the divorce.

On a tour of England, Nancy fell in love with the place. She even met the Astor family but not her future husband. After her mother died, Nancy's father encouraged her to move there with her young son. He said it would be in keeping with her mother's wishes and also be good for her younger sister Phyllis.

*I married beneath me. All women do.

*********************************************************************

Sources:

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Mourning Rituals and Customs in the Victorian Era - Part II

A Lady’s Life in Mourning

Mourning dictated that ladies limit, if not eliminate, their social activities. Men and children were also limited to avoiding large social affairs or parties while in mourning, but women were set apart as the idealized example of grief in the family and community. Upon entering mourning, women were expected to cancel all social activities. Callers were received only on a limited basis and other family members were expected to field people paying their respects in the home.

A woman expected to see only her immediate family, closest friends and her minister during this time. (Servants, if she had them, were an exception as they were seen daily and the workings of the household needed to continue, but servants were also expected to enter into mourning with the family at the death of their employer and remain in mourning as long as the family did).

While in “deep” mourning a lady was expected to avoid all public meetings, shopping trips and forbidden to attend teas or parties. It was also bad luck for a lady in “widow’s weeds” to attend a wedding. If necessary, she was expected to set aside her “deep” mourning for the event or be in absentia.

For ladies who carried them, calling cards were available, as was stationery for correspondence. Both the cards and stationery were very plain, white with black borders. The wider the border, the deeper the writer was in her mourning period. Calling cards in pale grey and lavender were also available for those in “light” mourning that wished to make their condition known as well.

As a lady reached the end of her “deep” mourning period she could recognize the change by enlarging her wardrobe and gradually returning to social activities (receiving callers, attending church functions and visiting relatives). Trim and jewelry could be added to an all-black ensemble and the “weeping veil” could be set aside. Eventually, the introduction of deep violets and greys could be used sparingly in the wardrobe, as well as white trims. Over a period of months, lighter shades of grey and purple could be used. “Light” mourning could consist of lavender, grey, white, and bits of black. Finally, other colors could be worn and the mourning garb abandoned.

Upon leaving mourning as a widow, it was acceptable – and somewhat expected – to remarry. If the lady had children, it was also a necessity.

Material sources on Mourning in America:

The After Life – Karen Rae Mehaffey

Hair Jewelry, Locks of Love – Michael J. Bernstein

The Trap Rebaited: Mourning Dress 1860 – 1890” – Anne Buck

The Victorian Celebration of Death – James Steven Curl

A History of Mourning – Richard Davey

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Antarctica

‘Polar stratospheric clouds’ formed last week when temperatures dropped below 176 degrees Fahrenheit. According to Renae Baker, a meteorological officer with the Australian Bureau of Meteorology at Mawson, Antarctica and who took the pictures on July 25, 2006, “Delicate colours produced when the fading light at sunset passed through tiny water-ice crystals blown along on a strong jet of stratospheric air.”

‘Polar stratospheric clouds’ formed last week when temperatures dropped below 176 degrees Fahrenheit. According to Renae Baker, a meteorological officer with the Australian Bureau of Meteorology at Mawson, Antarctica and who took the pictures on July 25, 2006, “Delicate colours produced when the fading light at sunset passed through tiny water-ice crystals blown along on a strong jet of stratospheric air.”

These kinds of clouds only occur at high polar latitudes and in winter. A weather balloon put temperatures at -189 degrees that day. “Amazingly, the winds at this height were blowing at nearly 230 kilometers (143 miles) per hour,” Baker said.

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20060801/ap_on_sc/antarctica_clouds_

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20060801/ap_on_sc/antarctica_clouds_http://www.aad.gov.au/default.asp?casid=23042

It was during the Victorian Era, a time of great exploration and invention, that the first explorers traveled to Antarctica for whaling and seal-hunting, and accidentally mapped out the continent. I won’t go into the horrible environmental- and animal- loss that occurred during this time, just the basic facts.

- In 1820 Nathaniel Palmer’s ship Hero sailed from the South Shetland Islands to “to study some unusual sightings on the horizon.” They stayed there overnight and “A dense fog settled over the ship and in the morning they found themselves at rest between two ships of the Russian expedition led by Bellingshausen. The Russian charts named Palmer Land in his honor.” [see http://www.south-pole.com/p0000073.htm for more on Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshaisen]

- The official US Antarctic Expedition didn’t occur until the 1838 Wilkes voyage [see http://www.south-pole.com/p0000079.htm for more on Charles Wilkes]

- It wasn’t until the 1897-1899 expedition that the first known photographs were taken of the 7th continent. Most of the crew deserted, the ship was trapped in ice, officers died, and at least 2 survivors went mad. It took the remaining crew months to cut through the ice to reach open water, before finally, 13 months after arriving, they were free.

- Between 1901-1905 there were German, Swedish, British, Scottish, and French expeditions.

- It wasn’t until 1909 that the first settlement, commercial of course, popped up on Kerguelen Island.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

VICTORIAN FASTLANE: Part 2, John Jacob Astor I

America's Gilded Age began with the legendary John Jacob Astor. He is called "the first truly diversified capitalist in America" by Brian Trumbore, editor of Stocks and News.com.

America's Gilded Age began with the legendary John Jacob Astor. He is called "the first truly diversified capitalist in America" by Brian Trumbore, editor of Stocks and News.com.Astor founded the dynasty that was America's richest family in the 19th century. The name Astor is still newsworthy. Recent headlines about the care of Brooke Astor, the 104 year old widow of John Jacob's great-great-great-grandson, William Vincent Astor (1891-1959), prove the Astors are still high profile.

Born in Waldorf, Germany, in 1763, the first American millionaire was given the name Johann Jakob Astor by his humble parents. He landed in this country with a small amount of money and seven flutes, which he promptly sold. While crossing the Atlantic he heard about the American fur trade. Astor went to work in his brother's New York butcher shop. He dreamed of supplying Europe's need for furs and bringing back the musical instruments so prized in America. In a few years, Astor went into fur trading beyond the western borders of the young nation. Within a year he was in London selling the furs he had purchased in America and buying trade goods to take back with him.

Back in America, he somehow found time to meet Sarah Todd. She came to buy furs from him and he was intrigued to learn she actually cut and sewed furs. They married and had three children, Magdalen Astor, 1788; John Jacob Astor II, 1791; and William Backhouse Astor, Sr., 1792.

In the 1790's Astor began investing in banks. By the age of 37, he was worth $250,000 - a fortune in 1800. He also owned a ship and imported wool and arms from Europe. In 1808, Astor founded the American Fur Company. One of his subsidiary companies established the trading post, Fort Astoria in 1811. It became Astoria, Washington. Astor succeeded largely through shrewd dealings with the Indian tribes and friendships with British officials who allowed him to branch out into the Northwest Territories.

By 1835, Astor retired from the fur trade to concentrate on New York real estate. A year later he opened the Astor House, a hotel on Broadway, adjacent to City Hall. It was called "astonishing" and a "marvel of the age." During its 80-year history, both Abraham Lincoln and the future King Edward VII were guests.

WHEN THE ASTORS OWNED NEW YORK, Blue Bloods and Grand Hotels in a Gilded Age, is the title of Justin Kaplan's new book. The Pulitzer Prize winning author's title is no exaggeration, since John Jacob bought acres of Manhattan farmland back when New York covered only the lowest tip of the island. This land, a part of which lies beneath the Empire State Building, added a colossal fortune to his legendary millions.

Kaplan's book focuses on the family's mania for building luxury hotels. As the fashionable people moved steadily uptown in Manhattan, the Astors built more sumptuous hotels, such as the Waldorf-Astoria, and introduced Americans to indoor plumbling, central heating, gas lighting, incandescent lighting, telephones, elevators, and air conditioning - as well as silver chafing dishes and velvet ropes.

John Jacob Astor died in 1848 at the age of 84. He was the richest man in America.

**********************************************************************

Brooke Astor is the author of three books:

PATCHWORK CHILD: Early Memories. Harper & Row, 1962.

FOOTPRINTS: An Autobiography. Doubleday, 1980.

THE LAST BLOSSOM ON THE PLUM TREE: A Period Piece. Random House, 1986.

Since the death of William Vincent Astor, Brooke Astor has given away 200 million dollars.

************************************************************************

Mourning in Victorian America

Every year Romance Writer's of America holds a national conference for its 9500 members. It includes workshops, agent/editor appointments, and an award ceremony. The Powers That Be change the location every year in an effort to accomodate those members who live in various sections of the country. This year, this past week actually, the conference was held in Atlanta Georgia. I managed to scrounge up the money to attend and gleefully stayed an extra couple of days to play--I mean research. One of the places I visited was Stately Oaks Plantation in Jonesboro.

http://www.georgianationalfair.com/RESULTS/WebDesignContestWinners/StatelyOaks/history.htm

Imagine my excitement when I found out I had come on the first day of a full month long display/tour of Victorian Mourning! My book Wicked Widow (shameless plug there!) is about a woman who breaks the rules and doesn't go into mourning when her first, and second, and third, husbands die, so this was right up my alley.

Anway, you'll see in the picture above that Stately Oaks is draped in black and has a wreathe on the door to tell the outside world that someone living in the house had died. In this particular case they were re-enacting the actual death of a child. Although they refused to allow me to take pictures inside the house--or a tape recorder--I did manage to jot down a few notes to share with others obsessed, or even mildly interested, in the Victorian period.

1.) The bottom floor (no one went upstairs so that didn't matter) was draped in black. This included musical instruments and mirrors.

2.) The casket was laid originally in the parlor. For a child's death a white rose (symbolizing innocence) was laid on top, with its stem broken, for the broken hearts of all those who'd lost someone so young.

3.) The parlor windows where the body was laid were draped in black.

4.) According to the tour guide, women went into mourning for 2 1/2 years. I have a book that contradicts that (Confidence Men and Painted Women by Karen Halttunen) with a 2 year period for widows. Regardless, during the first year a woman wore strictly black, from her shoes, to her hat, to her gloves and fan. After the first year she went into "second" or "lighter" mourning, gradually replacing various parts of her wardrobe with gray, violet or white.

Men wore black bands on their arms. That was all they were required to do.

5.) People brought food to the mourning family back then as they do today.

Those are the only notes I managed to jot down. The guide told me much, much more, but I couldn't remember it all, so I'll see what I can do later to write a little more about mourning rituals in Victorian America. Of course, much of this was already covered in Nicole's previous blog:

http://somethingvictorianblog.blogspot.com/2006/04/mourning-rituals-and-customs.html.

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

Spies Like Us

In the 1860s during the war between the states just how many spies were traveling back and forth across the lines. And just how did they accomplish this?

In my time travel romance work-in-progress, my heroine travels back in time into her past life. It seems she was a spy for the Yankees, who posed as a laundress in a Confederate camp to obtain information.

According to The Everything Civil War Book by Donald Vaughan, "Both sides had more than their share of spies--many of whom became both famous and infamous--as well as unique espionage technology."

Female spies like Belle Boyd, who spied for the Confederacy, used their feminine wiles to obtain information for their side and sometimes fell in love with their informants. http://www.civilwarhome.com/belleboyd.htm

Rose O'Neal Greenhow was a member of Washington society. She sent coded messages to Confederate military leaders on Union plans that were transported by women on horseback. http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/greenhow/

Friday, July 28, 2006

Quixotic Queries and Projecting Professionalism

But we dread writing query letters and synopses, even though they are the very first “impression” an editor has of us and our skill as a writer and our professionalism overall. Too often, we don’t give these valuable selling tools a lot of thought until it’s time to write one. And that can seem a pretty daunting task when you’ve just pulled a clean, warm copy of your latest MS off the printer.

But broken down into the necessary pieces, the query is not such a big deal. (Don’t tell my critique partners I said that – me of the trembling hands and sweaty palms at the very mention of the word “query”!!)

We all know the basics needed for a good query letter. Who is the story is about, minus the physical descriptions, what is going to pull them apart (Conflict!!! – please imagine this word as a flashing neon sign. Conflict!!) and how they are going to over come it. A little bit about who you are and why you are qualified to write this story and you’re done – right? Right!

Not so fast…

In recent months, in my capacity as senior editor at The Wild Rose Press, I have had the opportunity to see things from the “other” side of that envelope (or in my case, the e-mail inbox). So maybe it would be easier for me to talk about what not to do when querying an editor.

Dear Nicola…That was how the most recent query I received began. It pretty much went down hill from there. Call me old fashioned (it’s okay, I write historicals! I am old fashioned!) but having a stranger – let alone someone in a business situation – address me by first name just makes me bristle. Having them get that first name wrong just leaves me annoyed. Didn’t the author double check her information? Was my given name that difficult? Just a few weeks ago I sat through a three-hour-long high school graduation where nearly every other female student graduating was named Nicole or had Nicole for a middle name. Surely this author has heard it once or twice before. So what was this – a typo?

Slow down. Take your time. Have a friend or CP read the letter over. Set it aside for a day or two and re-read it before mailing it – and by all means, double check the accuracy of your information, right down to the spelling of the editor’s name and title.

Another query that comes to mind left me puzzled rather than interested in the author’s story. This author went on for several paragraphs in an attempt to convince me her story was appropriate for one specific line – a line that features non-American set historicals (i.e., regency, medieval). Yet the story was set in Colonial Virginia. This tells me she didn’t do her homework. Simply taking time to familiarize herself with our publishing company, and maybe a few minutes spent browsing the web site, would have been well worth her time. She would have seen that there was, indeed, a line for American-set historicals. Instead of wasting valuable “selling” time telling me how I could twist her story to fit this one particular line, she could have told me about the story itself. Do your homework. Familiarize yourself with the publisher you’re querying.

Lastly, mind your manners. Over at Wild Rose, we have a wonderful forum populated by our authors and wannabe authors where they share their successes, struggles and more. As editors, we often stop by to offer words of support, encouragement, and just to say hello. We enjoy the regular contact with the writers –heck, we’re writers, too, and the authors, in turn, have told us how much they like the “open door” feel of things on the forum. But it’s possible to get too comfortable. Not long ago an author posted a message complaining that she had sent a partial to an editor “like a month ago” and still hadn’t heard back. A month? A month you say? True our turn around time is a bit different than a big New York publishing house, and some editors aren’t quite as deluged as others and can respond more quickly --but posting the message to the forum was wrong. E-mailing the appropriate editor and inquiring about the status of her submission would have been appropriate.

Another author, mere minutes after I e-mailed her a detailed, two-page rejection letter pointing out to her exactly why I couldn’t accept her story as it was written and giving her in-depth suggestions on what areas of weakness she needed to focus on – went on the same forum ranting about editors “who don’t know what they’re talking about” and who asked her to “make changes that would compromise the historical accuracy” of her work. (Since when does learning the correct rules of PV affect historical accuracy?? ) She didn’t name me personally, but her intent was clear. Did she honestly think I wouldn’t see that message? What does that say about her to the other editors who saw it? She’s probably a wonderful person, but her angry, unprofessional response reflects poorly on her to everyone who sees it. Remember, whether you’re in a ladies room stall at a conference, or blabbing on a forum – you never know who may be listening.

One other common mistake I’ve seen is in the “bio” part of the query letter. You know, those last couple paragraphs where you say I’ve been writing for X number of years, am past president of my local chapter, etc. This should be about you, the writer. It’s important to convey to the editor how long you have studied your craft, how active you are in writing-related organizations, and any contests you’ve won or finaled in, particularly if it relates to the story you’re querying. But for me, personally, I don’t care if you have six goldfish, two cats and a dog named Ralph or that your husband is a retired marine biologist who can speak Dolphin. They aren’t querying me. You are. Save that stuff for the bio on your web site.

Perhaps my “favorite” query, or should I say the one that stands out in my mind as the worst I’ve ever received begins with “I’m querying you on behalf of so and so…” No mention of why this writer was querying me on behalf of someone else or the relation to that someone. Not to mention the whole sticky mess that opens up. Do you even know this person you’re querying for? And why couldn’t she do it herself? Too shy? Too busy? So for that one -- just don’t do it. Ever!

Thanks to Jenn and Christine for suggesting this blog, I never would have thought of it myself.

For more information about The Wild Rose Press, you can visit their website at www.thewildrosepress.com . You can also visit their “Greenhouse” for more information on writing query letters and synopses.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Researching Our Work

This is just and example of the problems of writing in a historical time period. None of us wants to use an anachronism. Research is very important. Fortunately, there are wonderful references and experts on writers loops to help.

Carolyn

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

The Engagement Ring

Queen Victoria also wore an engagement ring, a serpent symbolizing good luck. [6] And, of course, what the queen wore, society copied. As with many things from the Victorian Era, our traditions date from what they did.

Rings were often given as a sign of a marriage promise, though often only the wealthy could afford to do so. It wasn’t until 860 AD that the Catholic Church mandated all marriages were to be symbolized by a ring. “In 860 Pope Nicolas I decreed that a ring was a requirement to signify betrothal or engagement and it was also stipulated that it should be a gold ring…” [1]

But that was a wedding ring, not an engagement ring. The first recorded occurrence of a woman receiving a diamond engagement ring was in 1477. The Archduke Maximilian of Hamburg gave it to his betrothed, Mary of Burgundy. [2] Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find anything on the ring itself.

“By 1890 engagement had become a distinctive stage in the transition to marriage—a stage with its own rites of initiation (the announcement), its own ceremonial object (the engagement ring) and its own rules of conduct” [3]

A diamond ring symbolized innocence; sapphires, immortal life; rubies, affection; emeralds, success in love. No pearls or opals - they were considered harbingers of bad luck. [4]

By the mid 1870’s colorless stones were more fashionable. By the 1880’s, diamonds were considered far better taste than the brightly colored stones of the 1860’s. And by the 1890’s, colored stones were completely out of fashion. In 1857 diamond mines were discovered in Brazil, and in 1867 they were discovered in South Africa. [5]

1. http://www.hkjewellery.co.uk/default.asp?Page=engagementrings-history

2. http://www.circa1930s.com/c30content/c30-historyengagementrings.htm

3. Hands and Hearts: History of Courtship in America by Ellen K. Rothman

4. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Victoriana: A Comprehensive Guide to the Designs, Customs, and Inventions of the Victorian Era by Nancy Ruhling and John Crosby Freeman

5. Victorian Jewelry by Margaret Flower

6. http://www.hudsonvalleyweddings.com/guide/rings.htm

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Bonnets & Hats

Thursday, July 06, 2006

Let’s see the country

By bringing “harmony the heretofore jarring discords of a Continent of separated peoples,” Bowles promoted travel as patriotism – businessmen promoted it as tourist dollars. However, with travel becoming easier and more accessible to the masses, it also helped transform the American West from cattle towns to industrial cities.[2]

Queen Victoria promoted her own version of cross-country traveling when she first made the trip – partly by the new invention of train – to Scotland in 1842. “Their exploration of Perthshire, walking, reading and deer-stalking, was so pleasurable that they returned annually. In 1852 they bought Balmoral and had the castle built. The Queen’s Scottish memoirs and paintings of the scenery were extremely popular and her love of tartan ensured publicity and a healthy business for the tweed industry.” [3]

Tourist dollars provided a boom to Scotland. If the Queen went to Scotland, so, too, could everyone else. When the railroad extended north in the early 1850s, travel became much easier for everyone as more and more people traveled both to and from Scotland to seek their fortunes.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Bowles_%28journalist%29

2. The New York Times Sunday Book Review, July 2, 2006, Bruce Barcott

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/books/review/02barc.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

3. http://www.scotclans.com/history/1842_victoria.html

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Nineteenth Century Rail Travel

Rail travel’s hypnotic rhythm, unique smells, and the sense of adventure stir the imagination, but a few basic facts offer enlightenment to the advent of personal travel by train. The first commercial rail cars were in England in—believe it or not—1630—and were drawn by horses over wooden rails to transport coal. By the mid 1700’s, iron rails had replaced wood. The first steam-powered land vehicle built by Frenchman Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot in 1769 laid the foundation for future locomotives.

In the United States, Congress had invested heavily in the Eerie Canal and other waterways and resisted the idea of railroads. Public opinion eventually won. In 1827, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first railroad charter granted in the United States. By 1852, its three hundred miles of track made this the longest railroad in the world. At first used only for transporting goods, passenger service soon developed. Once the transcontinental rail lines were completed in 1869, America was opened to settlers from all over the world.

A wide variety of facilities awaited passengers. On some lines, the coaches were little more than rough structures that offered no comfort. Wooden benches with high backs—many times without a cushion of any kind—tortured passengers on a long journey. By comparison, it probably was no worse than riding in a wagon, and the train made the trip faster. Other lines had coaches with padded bench seats, and still others with movable armchairs. Toilets sometimes were no more than a curtained off chamber pot offering minimal privacy. Summer forced passengers to choose between tolerating soot, smoke and dust with the windows open, or sweltering with windows closed. In winter, passengers near the potbellied stove roasted while those at the other end of the car froze. Sometimes cars were reserved for women and their escorts and no males traveling without family were allowed in these coaches. Often as not, all travelers jumbled together.

Soon lines developed luxury cars designed to mimic fine hotel lobbies. A major advance occurred when George M. Pullman began his line of luxury cars called Pullman Palace Cars. His company developed hotel cars, sleeping cars, club cars, dining cars, and drawing room cars. According to George Deeming, Curator of the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, these coaches required high fees similar to luxury hotels and were not available to the masses. The first Pullman sleeping car appeared in 1859 at only forty feet long. It was a reconstructed wooden day coach with metal wheels and a low, flat roof. A tall man was likely to bump his head. It had ten upper and ten lower berths with mattresses and blankets, but no sheets. A one-person toilet stood at one end. Two small wood-burning stoves furnished heat and candles provided light.

In 1865, the first real Pullman sleeping car came into service. It featured the first upper berth that folded out of sight for daytime, heated air from a hot air furnace under the floor, upper deck window ventilation, and roomier wash rooms. This car had black walnut interior with inlay or mirrors between windows. In another ten years, the length had increased to seventy feet with even more elaborate wood interior and luxurious plush seats. Pullman coaches offered privacy with curtained off sleeping quarters or wood paneled compartments, and separate toilets for men and women.

At first trains stopped for passengers to debark and eat or even to spend the night in a hotel, as depicted in stories of the Harvey Girls and Harvey Hotels. Time always pressed diners and the traveler had no control over what food was available. Some dining places—due to necessity for speed—served the poorly prepared rations. A few sites deliberately cheated travelers with slovenly hygiene and half-cooked food. Others, such as Harvey, maintained high standards. At a dining stop, passengers rushed off the train for a hasty meal, then rushed back on board when the gong sounded. Travelers were forced to gulp and run if they were lucky enough to beat the crowd and get served.

The advent of the dining car meant passengers could eat a proper meal on board, provided they had the cash. The first dining car, the Delmonico, came into service in 1868 on the Chicago & Alton line. Within ten years, they were on most lines. In 1878, a full meal cost seventy-five cents, at a time when a common laborer made less than that for an entire day’s work. Pullman dining cars marketed luxury. Fine tablecloths had PPCC woven into the cloth, for Pullman Palace Car Corporation. Uniformed servers delivered well-prepared food to tables set with fine china, crystal and silver. Some cars had fresh flowers in built-in silver vases at each table.

Shipping also changed, with railroad cars providing speed and more protection for cargo than horse or mule drawn wagons. For a fee, rail cars could be temporarily or permanently customized for specific products. In the Kansas, Texas & Pacific Railroad Museum in Dennison, Texas, books intended for railroad employees detail modifying and repair of shipping cars for a variety of purposes.

The Great Western Railway constructed a bridge across Niagara Falls to link the United States and Canada in 1855. It was not until 1882 that a bridge crossed the expanse of the Mississippi River at Memphis. Prior to that date, trains departing West from Memphis were ferried, one or two cars at a time, across the Mississippi.

In 1869 (this date really surprised me) the first refrigerated rail car appeared and soon allowed the transport of fresh produce and meats. One of the significant changes brought about by the railroad in the West was elimination of the great cattle drives to the Midwest or Northern markets. Centralized rail shipping allowed ranchers to ship from locations near home.

After the Civil War, train robberies occurred, particularly West of the Mississippi River. Former soldiers carried out many of these, some returning home and others looking for an easy income. Usually no one was injured, but watches, wallets, money and jewelry were collected from the passengers. Sometimes robbers forced passengers to drink liquor or sing as added aggravation.

Towns grew and flourished along the railroad. Those communities bypassed by the line often withered and disappeared. Competitions arose between communities to attract the railroad, often with bitter result. For those fortunate enough to live near a rail line, products never before seen became available. Railroads brought easier travel, dependable shipping, and availability of goods to change America forever.

For those interested in more details about rail travel, consult your local library for their selections or ask for one of the following:

The American Railroad Passenger Car; John H. White, Jr. 1978, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 21218.

Hear The Wind Blow: A Pictorial Epic Of America In The Railroad Age; Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg, Grossett & Dunlap.

The Overland Limited, Lucius Beebe, Howell-North Books, Berkley CA. [This has a large section on Pullman cars.]

The Pacific Tourist: Adams & Bishop’s Illustrated Guide of Travel, The Atlantic To The Pacific; Frederick E. Shearer, Editor; Adams & Bishop, 1881.

Railroads Across America; Mike Del Vecchio, 1998, Lowe & Hold, Ann Arbor MI

The Railroad Passenger Car; August Mencken, Johns Hopkins Press. [This includes personal accounts by passengers over 150 years.}

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Visit Caroline Clemmons at her website at www.carolineclemmons.com for release information, excerpts, recipes, writing tips, and her contest.

Saturday, July 01, 2006

The Cowboy Mystique

Let’s start with that honor-bound “knight of the plains”, the cowboy.

The earliest cowboys were a far cry from the image that probably jumped to your mind with the very mention of the word. For one thing, they spoke Spanish, and rather than the stereotypical chaps and Stetsons, they wore brightly colored costumes and did most of their riding, roping and branding in the Mexican provinces of Upper California and Texas. They called themselves Vaqueros (the pronunciation of the name is similar to that of the word “buckaroos” which is where the term originated) from vaca, the Spanish word for cow.

But these vaqueros created the legacy that lives on in the American cowboy as we think of him today. So where did that code of conduct come from that tells us – in one simple word – that this is a man of noble deeds and few words?

When defeated Texans returned to their run-down farms after the civil war ended in 1865, they found a land teeming with wild longhorns (a breed of wild bovine that resulted from the breeding of the American cow with Spanish cattle. These guys were lean, slab-sided—and ornery). A longhorn steer worth four dollars in Texas could fetch as much as $40 up north where there was an insatiable demand for beef. Cattle were also needed to feed army troops, railroad crews, as well as Indians newly confined to reservations. A new western industry was about to boom – and the cowboy would play a central role.

Most cowboys were young, from their late teens to early twenties. And they were a varied lot, made up of both former Union and Confederate soldiers (a large percentage were ex Confederates from Texas), Mexican-Americans and a small percentage of African Americans as well. Some were simply young men looking for excitement.

A cowboys’ past was a private matter – the origination, perhaps of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” He was just as likely to be a preacher’s son, a dropout from an Eastern university or the youngest son of an English nobleman sent to the American West to make something of himself as he was to be a wanted man. But the way he threw a saddle over his horse was all his peers needed to know whether he understood his business or not. That was all that mattered.

The cowboy was no mere farm hand. He had to be a superb horseman, excellent ropester and tough enough to subdue a 1,000 pound steer. It goes without saying that such a man would carry himself with pride, knowing he was admired – even envied – by other men who hadn’t the wherewithal to withstand his nomadic lifestyle. Spring and fall would find him on roundups – collecting the cattle and driving them in so the calves could be branded and bulls castrated in the spring; cutting marketable steers from the herd in the fall (females were kept for breeding). And that wasn’t even the dangerous part.

On the trail, a cowboy faced a multitude of dangers ranging from violent weather to raging rivers, illness and disease, marauding guerilla gangs and even groups of angry farmers determined to keep the longhorns, which carried a virus fatal to other breed of cattle, away from their fields. Stampedes were also an ever-present threat. Two or three thousand longhorn steer could be controlled only when they wanted to be and were capable of erupting into mass hysteria any time of the night or day, particularly during bad weather. So no matter how cold, wet or sleep-deprived a cowboy might be, he had to be prepared to leap into the saddle at the first rumble of a herd on the run.

Spending months on a trail drive meant he would go long periods of time without seeing a woman, let alone touching or speaking with one. Since his lifestyle precluded him from forming romantic entanglements, (marriage and family was out of the question as long as he remained in that line of work) the only women he could hope to meet on equal terms were prostitutes, or the “soiled doves” awaiting his arrival at the end of the trail. Because of this, his attitude toward “respectable women” was primly Victorian, almost worshipful. And when the opportunity to be in the company of a decent woman arose, the cowboy would go to great lengths to make the most of it.

As one story goes, neighbors from a distant spread attended a dance at a Texas ranch one rainy evening, bringing their newly-hired governess with them. When leaving for home with her employers, the young governess forgot her overshoes. The following Sunday, an eager young cowboy showed up at their door and presented the young lady with one shoe. “But there were two,” she protested. “Yes,” answered the cowboy, “I’ll bring the other one next Sunday if you don’t mind. And ma’am? I sure do wish you was a centipede.”

In 1886 a severe drought that left the herds in poor condition by summer’s end was followed by a series of blizzards. Livestock on the range was devastated, with some ranches losing up to ninety percent of their stock. This was the beginning of the end of the open-range cowboy.

So no matter what image his names brings to mind for you, the cowboy was, courageous, strong, dedicated, trail-wise, and respectful of women. A true American hero.

For more information on cowboys and the Wild West I recommend:

“The Wild West” by Warner Books

“Cowboys of the Old West” – by Time Life books

Monday, June 26, 2006

Victorian Ladies' Outerwear

Thursday, June 22, 2006

Gypsy Troupes, Part II: A Royal’s Entertainment

The Spanish Eugenie was a lesser member of Spanish royalty (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eug%C3%A9nie_de_Montijo), which afforded her time to spend with her adoring father - the Grandee Don Cipriano - on wild excursions. Riding horseback into Gypsy encampments for lengthy stays in the outlying countryside, Eugenie became comfortably familiar with the troupes’ customs and culture.

Eugenie learned the music and dances of the Gitanos, which were the Spanish gypsies, and even the fortune-telling skills that she later used when traveling incognito. Historically, Spaniard aristocracy traveled in disguise, especially disguised as gypsies. A number of modern societies can be found which are preserving the history of gypsies; one which describes the various groupings and American settlements is located at http://www.gypsyloresociety.org/interact.html

In the book Crowned In A Far Country by Princess Michael of Kent (ISBN 0954327217), an incident of Eugenie’s youthful adventures is told masterfully by this seasoned storyteller. Eugenie and another female friend (no name given) were traveling in Seville, Spain, posing as a pair of wild gypsy women. They were staying in their own tent, having a grand adventure, entertaining passing gentlemen with gypsy dances and tossing wantonly flirtatious glances. The two ingénues eventually revealed their identity to two smitten British gentlemen, as the story goes.

As the influential Empress of France, Eugenie notably favored traditional Spanish and Gypsy music. (She was even described at times as hopeless when it came to classical music.) Even as her tastes in fashionable attire and her reddish-gold hair color started major trends that swept more than one continent, her tastes in musical choices and entertainment were also being copied and even decried by wagging tongues.

Scandalously, Eugenie often appeared in wild costumes for entertainment, including gypsy-derived styles. Until Eugenie became the focal point of blame for the failure of the “Mexican Adventure” and until the execution of the Archduke Maximilian of Austria Emperor of Mexico, Eugenie ran a lively and exciting court. Upon the death of the Archduke, she and other members of the court went into official mourning. After 1867, therefore, more somber styles of music and fashion and entertainment permeated the French court, ending an era of wilder fashion and entertainment as inspired by Eugenie's love of the Spanish and Gitanos. Eugenie even stopped purchasing extravagant gowns from the House of Worth dressing less frivolously and extravagently. Until 1867, then, Eugenie’s Spanish heritage and gypsy flair had created some exciting trends during in the Victorian era.

By Kristin-Marie

Monday, June 19, 2006

Modern Innovation

The 1870s, of course.

The Tower Pedestrian Subway under the Thames, built by Peter W. Barlow and James Henry Greathead took only about a year to complete. This wasn’t the first subway tunnel, that was the Thames Tunnel at Wapping completed in 1843 meant for the future London Underground. However, it was only the second due to problems encountered by that tunnel’s creator, Marc Brunel. Yet at 34, Greathead “tendered for the construction of the shafts and tunnel for £9400, devising a cylindrical wrought iron shield forced forward by 6 powerful screws as the material was excavated in front of it.”

According to Nicholas Bentley in The Victorian Scene: 1837-1901, “it runs a quarter of a mile beneath the Thames between Tower Hill and Bermondsley.”

(Go here to view pictures of the tunnel: http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/engineers/tunnel1.html)

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Victorian Birth Control

By the early 19th century they were being used by the upper-classes of England and France as contraceptives and were available as early as the middle of the 18th century at Mrs. Phillips store on Half Moon street in London. In the U.S. sea captains kept ships stocked up to protect their sailors from disease. In the early 19th century they were advertised in newspapers and available through the mail in the U.S.

Condoms, known by various names such as skins or safes, were originally created using animal membranes. The method used to make the better ones made them thin, strong, and also expensive—as much as 1$ per condom. Because of the cost, early condoms were washed out and reused. By mid-century were being made using vulcanized rubber. The prices dropped significantly, $3-$6 a dozen. They were readily available at druggists and through the mail.

The rubber condoms weren’t always effective however. Without our modern controls rubber condoms could be weak in spots which would cause them to break, and some might even have holes. They had seams running down the middle and were so thick as to seriously reduce sensation. Still, they were better than nothing.

In 1873, with the help of crusader Anthony Comstock, advertisement for birth control was outlawed under the obscenity laws. It was also illegal to send obscenity through the mail, which included condoms. However, there is anecdotal evidence through diaries and records that condoms were still available if a person knew where to find them.